engineering. tomorrow. together – that’s how thyssenkrupp makes its brand promise a reality. For us, ‘tomorrow’ means constantly researching new raw materials and production processes in order to meet the future needs of the market and our customers.

(Text: Judy Born, Photos: Dominik Asbach)

Mobility is and will remain one of the megatrends of the future. It is an expression of freedom, independence, self-determination. Today, the desire for mobility is primarily satisfied by the automobile. And that is not likely to change in the foreseeable future, because any time enthusiasm for mobility decreases, it is balanced out by an increase somewhere else. This is true in part because of another megatrend: population growth.

More than a million cars are on the road worldwide right now. It remains to be seen whether we will soon be filling our tanks with gasoline or electricity or powering our cars with hydrogen or sunlight, and whether we will be doing it ourselves or letting robots do it for us. The car is the ultimate individual mode of transportation, even if it won’t necessarily be the only one in the future.

New materials are needed

As a result, car manufacturers need new ideas and models. Automobiles have to become more environmentally friendly and use resources more efficiently. They need to offer more comfort and safety. And they must become less expensive to produce and maintain. For the Steel division of thyssenkrupp, this means orienting the division’s materials to the current and future requirements of automobile production. For example, the division needs to develop types of steel that offer greater potential for lightweight construction and a broader range of forming options, and in certain parts of the chassis it needs to offer both increased stability and greater flexibility.

Progress in these areas is plain to see at Westfalenhütte in Dortmund, the site of an important branch of thyssenkrupp’s Research and Development division. It is here that the achievements of materials developers are cast in steel and become a reality. “At the end of the day, we’re a miniature smelting plant,” says Jens-Ulrik Becker, head of process development and pilot production. “Steel is smelted here just like at a big plant. It’s annealed and hot and cold rolled, the only difference being that the quantities are small.”

The ideas for new materials come not only from the automotive industry, but from thyssenkrupp’s Steel division as a whole. “Our internal customer base, if you will, is not limited to the materials developers from the Steel division. It also includes our coworkers in precision hot strip, tinplate, heavy plate, and electrical steel,” says Becker. “That’s because we are able to reconstruct many different facilities and produce both the thinnest tinplate and the thickest heavy plate.” Ideas are in plentiful supply at the company, and there is always plenty to do, he reports.

The search for ideal surfaces

However, a new product at thyssenkrupp still has to pass through additional stages before it is ready for the market. The usual procedure is for Becker and his employees to pass the new material on to the Surfaces pilot production facility, where Bernd Schuhmacher and his team work on coatings for new steel grades. This is a crucial job, because more than 80 percent of thyssenkrupp’s rolled steel destined for automotive customers undergoes surface treatment prior to delivery.

The chemical composition of a steel grade strongly influences its coatability. “For example, we have a hot dipping laboratory where we can selectively reproduce the hot-dip coating process for new steels in small quantities,” says the head of the New Surfaces and Pilot Production department. The same holds true for the coil coating lab, where organic coatings are applied by means of rolling. These high-performance laboratories make it possible to save on a lot of costly operating tests, which now only become necessary once the product has achieved the required degree of maturity in the laboratory.

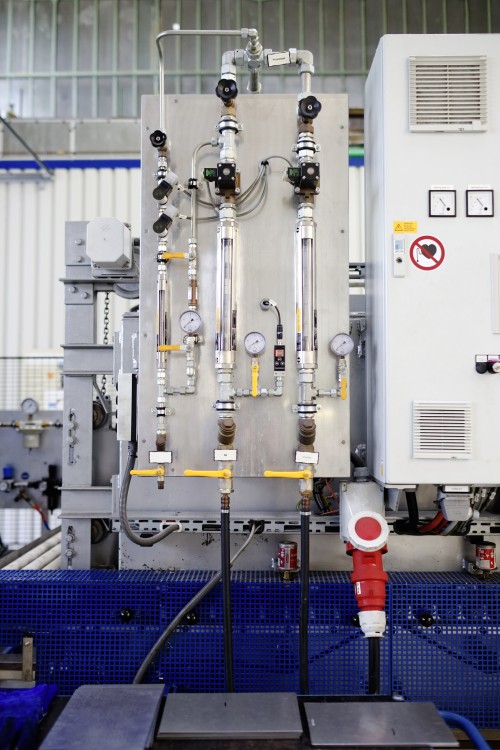

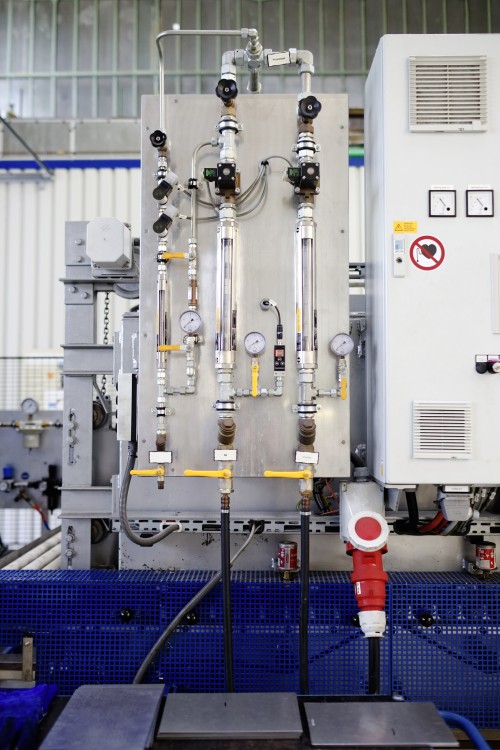

Another of the team’s core areas is the BPA 300 strip pilot plant, a modularly designed research facility for 300-millimeter-wide slit strip, which runs through the machine at a rate of 60 meters per minute. The facility is able to test a large number of coating and cleaning methods that have yet to become established in the steel industry. It functions as a kind of midwife, so to speak, for a number of different developments. One example is the zinc-magnesium product family, a hot dipping process that has recently come to occupy a regular position in the steel portfolio as an outer shell coating for the automotive industry.

New material properties require innovative technologies. “Hot dipping and organic coil coating have really reached their limits in this regard,” reports Schuhmacher. “By contrast, vacuum deposition, where the coating is applied as a thin film on flat-rolled steel, markedly increases the degree of flexibility in choosing the coating process.” Developing and industrializing a technology like this is exactly what the strip pilot plant was built for. “Here at the pilot plant we can run tests under conditions that closely approximate those of large industrial plants. If it works here, it should be possible to develop an industry-compatible process.” And if not, the tests will help set the right priorities at an early stage.